Sweetness

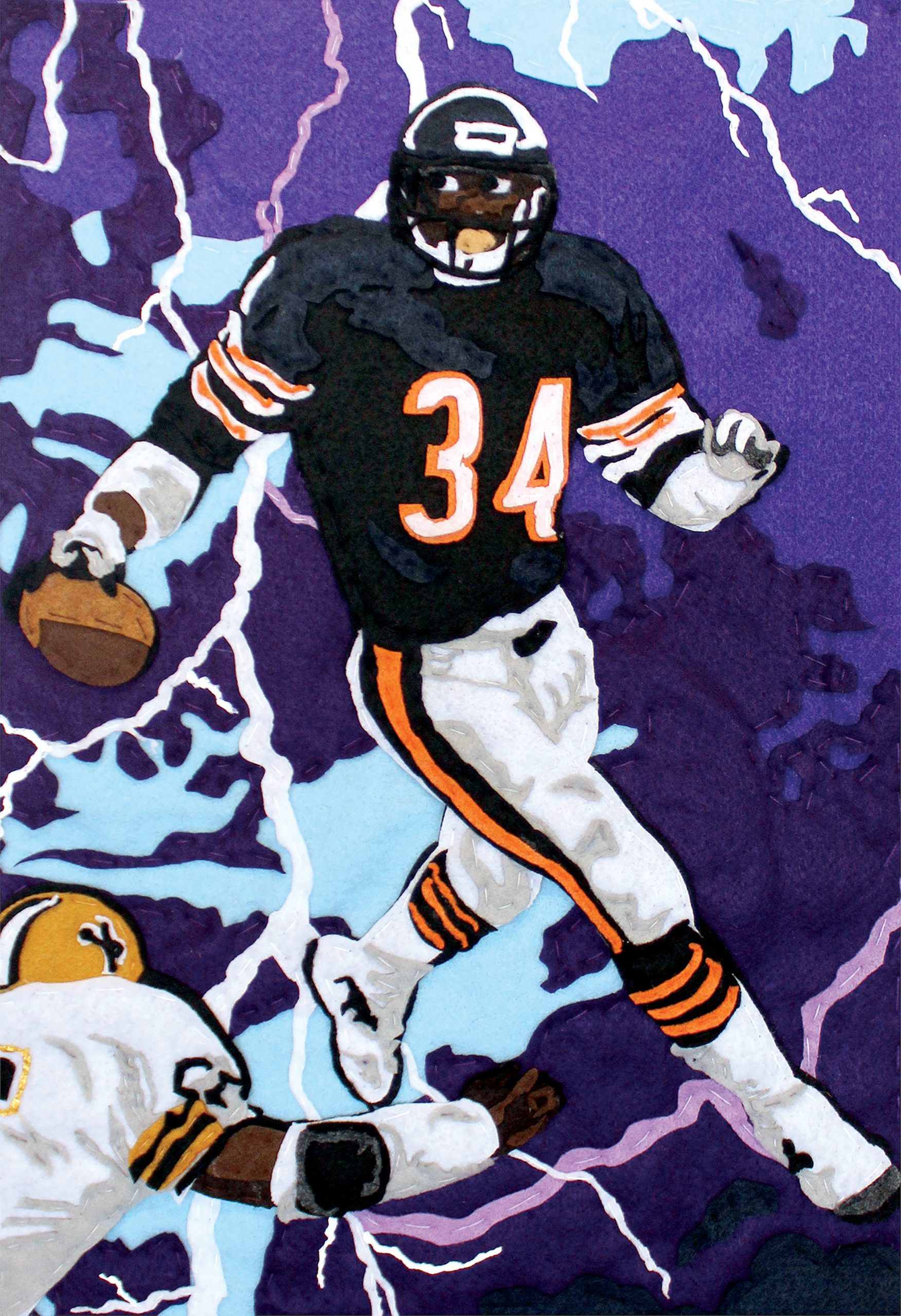

In a game played by men, Walter Payton played like a god. Or so was the allure that he presented. Not the biggest of athletes, Payton didn’t redefine the running back position in the way that Jim Brown did, nor did he set records that would stand the test of the time. But more importantly, he exemplified the most remarkable characteristic in a human being — heart and soul. Payton did carry a genuine heart, and having once grooved on Soul Train, he also carried swagger. He’s the man your parents want you to model your life around, and one the NFL has honored as the marker for every seasons Man of the Year award. But as we look back on Payton’s life, we begin to understand that no man, nor any god in the canon of antiquity, was perfect. His story, like so many others was cut tragically short and was immortalized as a result.

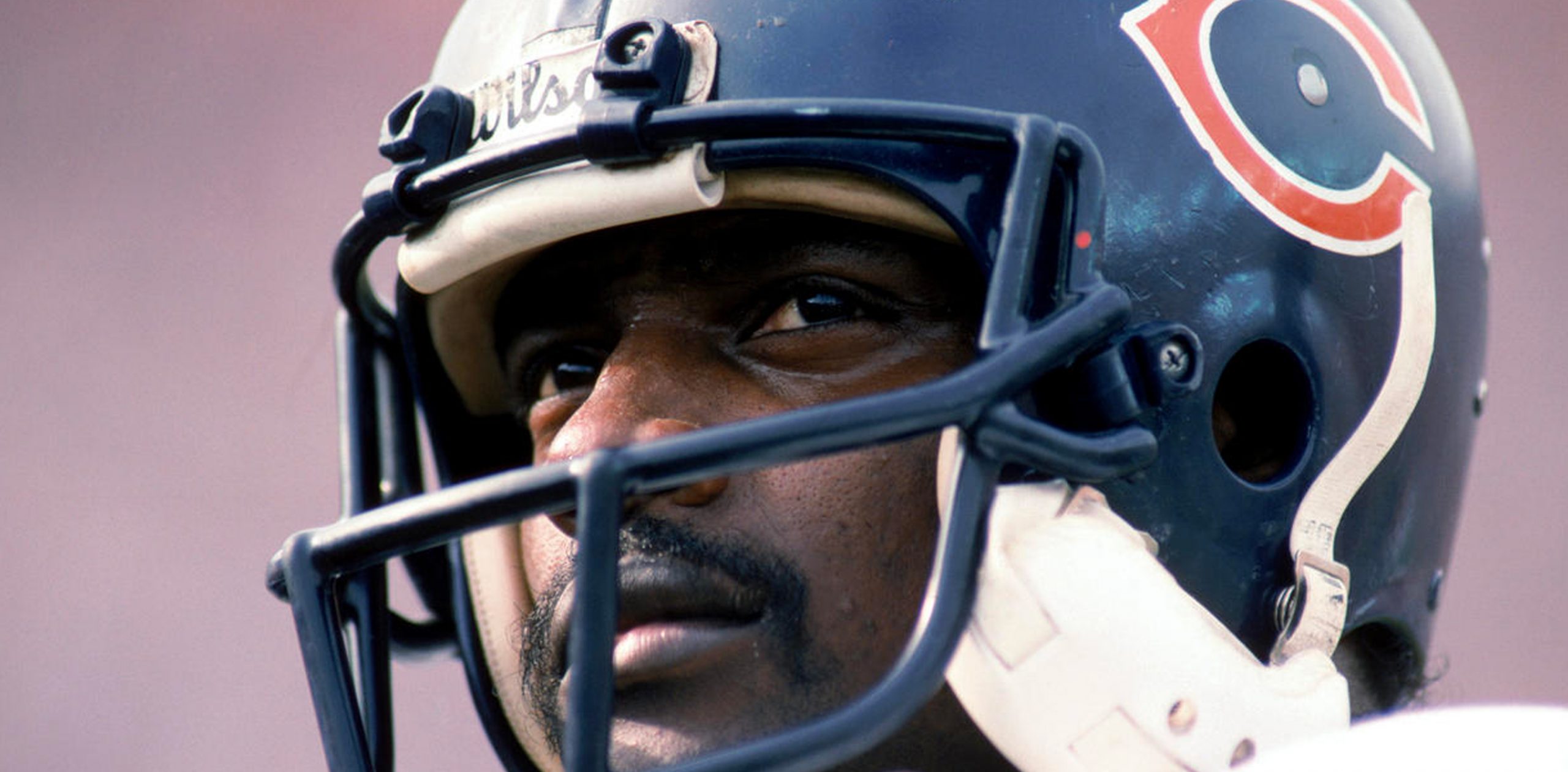

Born in Columbia, Mississippi in 1954, Walter Payton was well-accustomed to racism, but never paid it much attention. Columbia High, where he’d attend, didn’t even desegregate till his junior year, but instead of reverting to the growing cries of ‘black power’, he’d begin to bridge the culture gap on his football team through casual jokes. A precursor to the prankster we remember him as today, he had a certain carefree charm that could fix any day. On the football field, though, he was a force to be reckoned with. He’d go on to play at Jackson State, an HBCU where he’d flourish into the fourth overall pick by the Chicago Bears in the 1975 NFL Draft.

Many players close to Payton would sometimes characterize his demeanor as childish, maybe even charming. However, sweetness is perhaps the best way we all remember him. He’d joke with teammates, one time shouting, “your sweetness is your weakness!” then writing it on the blackboard before every practice. He amused some and annoyed others. The moniker would fit better than a series of names from ‘Bubba’ to ‘Little Monk’, as Payton biographer Jeff Pearlman would account in the aptly titled book, Sweetness.

"Never die easy."

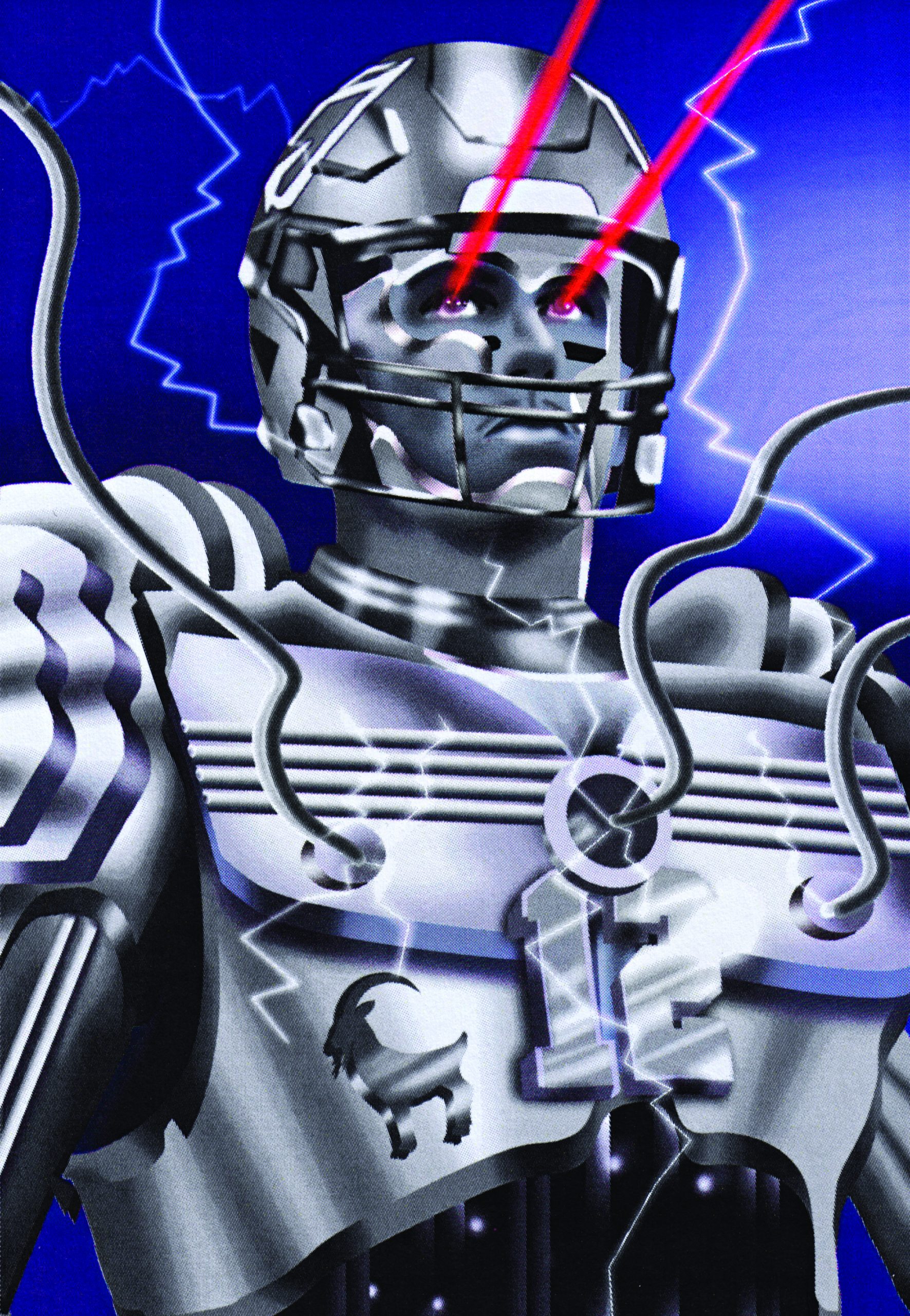

“After a lifetime of imperfect monikers that never quite worked, here was one that fit perfectly. The smiley, goofy, soft-spoken Payton was a sweet person. The cutting, dashing, swiveling Payton was a sweet runner.” Regardless of the fun and games, this wasn’t the mighty Bears of old — even worse than we know them in the present day. For all intents and purposes, the Chicago Bears were a dumpster fire in the ‘70s, a laughingstock that was a shell of its former self. Pearlman added that the Bears would go from a team whose history was “the early history of the game itself”, to “a forgettable second-tier club.”

Payton was drafted precisely to fix that. His first game, however, would be a disaster as the Bears had no offensive line, no leadership, nor any care from the team to fix it. With eight carries, Payton would log zero yards in his first game, which would result in a brushfire by the Chicago media. His early seasons would largely mimic that of the Bears—forgettable, with a conveyor belt of coaches that were more concerned about their drinking than winning.

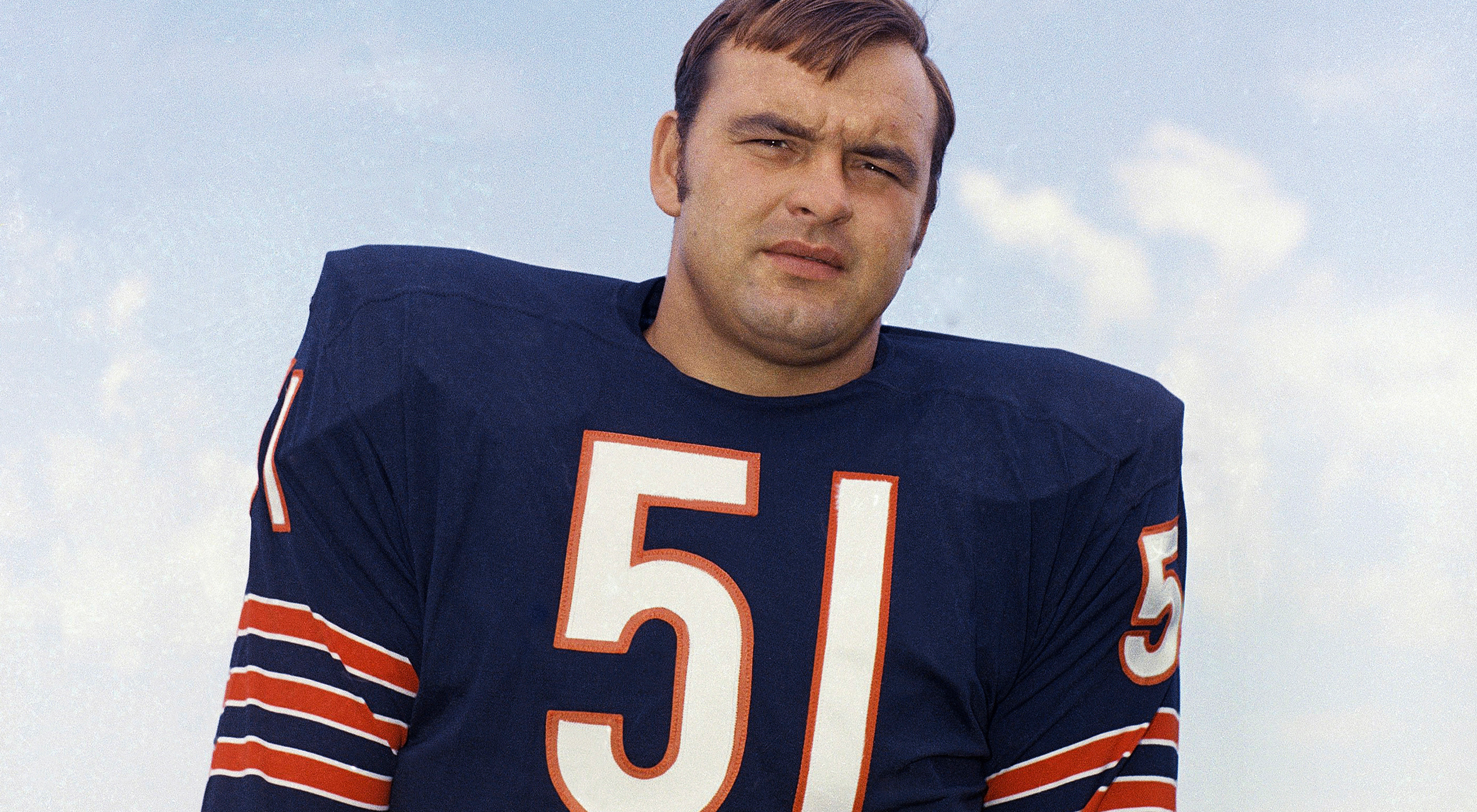

Nonetheless, players, such as linebacker Larry Ely, began to notice the sheer talent and work ethic that Payton would show in each practice, starting with his athleticism. “When he got tackled, four…five…six people would have his legs, his neck, his arms, and he’d bounce back like a rubber ball to the huddle. How in the world did his ligaments and muscles take the pounding and bounce right back? You looked at him and wondered how any human being could be blessed with such a body.” This drive would fit right into his playing ethos: “Never die easy.”

Like Columbia High, the Bears were also bitterly divided between the races. Payton would intervene in his usual jokester way, sometimes to the chagrin of his teammates. Rookie quarterback Bob Avellini would note that Payton was a “nice guy, without a doubt, but childish. We’d be working out in shorts and he’d pull your shorts down. Maybe it’s funny the first time. By the fifth time, it’s not.” This childishness would become a prevalent theme within his life, as his hidden insecurities would continually resurface, such as his constant need for approval. Avellini recalled a game where Payton’s backup would log in a “forty-yard gain, and everyone was clapping. But Walter was pissed. He turned to me and said, ‘Those are my yards.’”

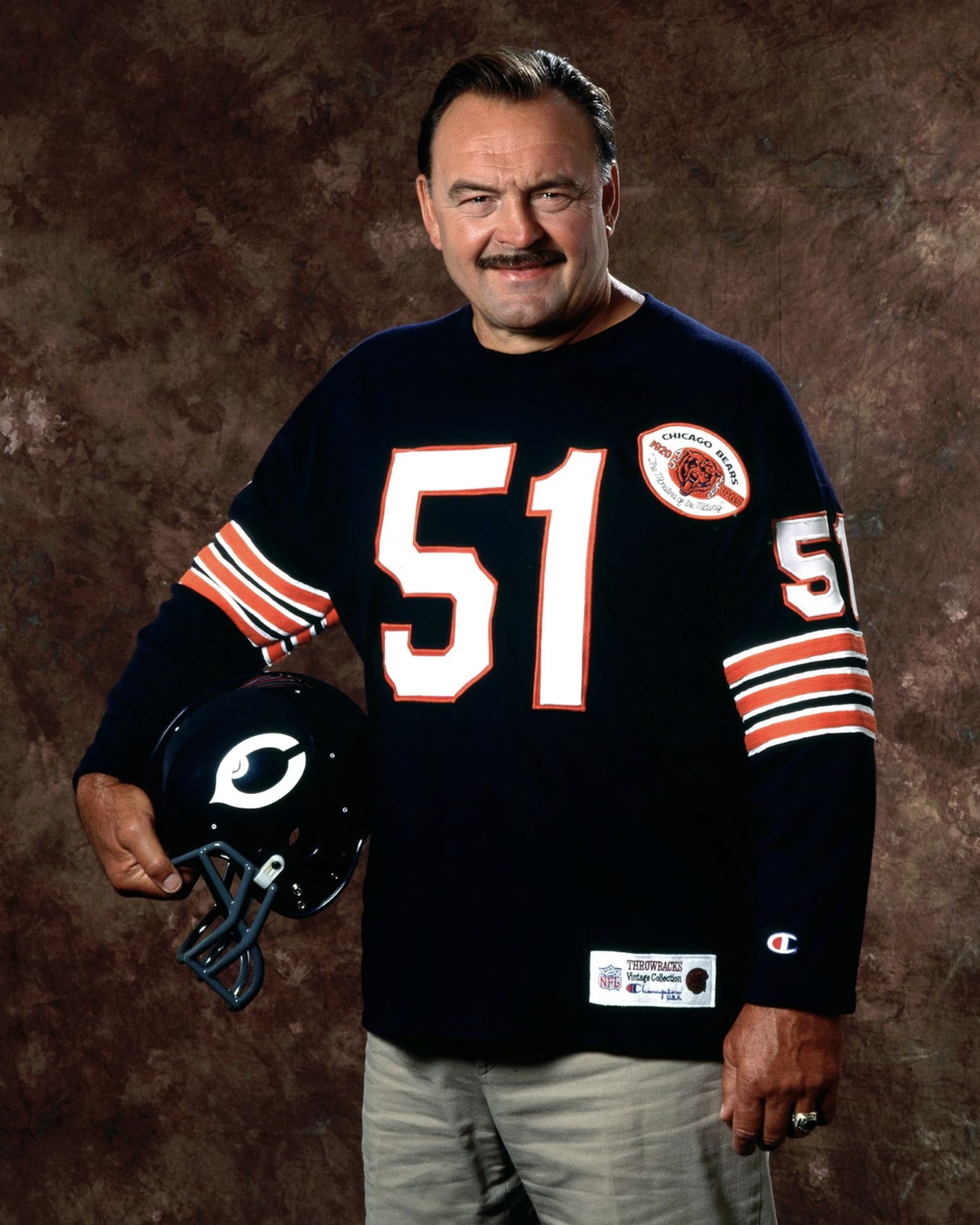

Having once chased and broken Jim Brown’s iconic rushing record, sometimes the Bears could not count on Payton when needing to stop the clock. Instead of running out of bounds he would simply keep pounding to pad his own stats. He “could be selfish in some very ugly ways,” recalled another team member. This selfishness would hark to his famous outburst in Super Bowl XX, where he felt he was snubbed a touchdown, despite a handful of players, including the giant teddy bear in William “Refrigerator” Perry, who logged arguably the most memorable score during that game. On one end, it would make sense that Payton, who literally battered his body and carried the franchise for eleven years till that point, would seek the validation of a Super Bowl touchdown. However, on the other end, as Bears coach, Mike Ditka would reassert: “I can understand [the whining] if you play golf or tennis or billiards. You’re one-on-one with the world. But we’re a forty-nine-man sport.”

Payton indeed was a phenomenal runner, with a certain fire that could seldom be extinguished. But what he was running from, still continues to puzzle the football community. There always seemed to be a void that he could not fill, not even his twenty-three year marriage to Connie Norwood could bring a semblance of balance. While the running back never partook in drugs or heavy drinking, his drug of choice was fast cars, shopping, hunting, and fame. Contrary to public opinion, Payton, too, succumbed to a vice that taints many star athletes—adultery—as he’d meet a young woman by the name of Angelina Smythe at a 1984 auto show.

"Payton was the clichéd celebrity—surrounded by admirers, yet alone."

He’d regularly call her to fill the emptiness of his marriage, that was far past a physical lust, but an emotional hunger too. For his marriage with Connie was strictly “mechanical” in that he certainly provided all that his wife and kids needed, but would spend the majority of his off-time elsewhere. Payton ended up impregnating Smythe, who he’d in-turn cut off in secrecy by signing a $50,000 trust along with child support. Despite constantly showing love to his two kids, Jarrett and Brittney, Nigel was not so lucky.

It was evident to his small circle of true friends, that Payton suffered from severe depression, that on occasion could have easily ended in suicide. Despite the numerous fans that donned his famous 34 jersey, or the acclaim from his peers, no one really knew Walter Payton, the man. Not even his wife, who upon the death of her husband, refused to believe the truth of Nigel Smythe. Connie had a fixed narrative of the entire marriage, where she always believed that Walter was a devout Christian—which he once was—but the emptiness that came with his fame—tainted that reality. Friends would urge Payton to seek therapy, in which he’d play off—heroes didn’t need therapy. It’s a tragic tale to a genuinely good man who did a great deal for his fans and community. Make no mistake, Walter Payton was a great player and a great man, one that was constantly giving back to the community, by supporting children’s literacy programs and would further help these groups through the Walter Payton Foundation. But often times, even the greatest of men fall to unfortunate mistakes.

Toward the later years of Payton’s life, he sought to instill lessons within his kids that may combat the corruption that comes with money and fame. Especially with Jarret, who he’d have working summers at Payton Power, where Jarrett would tirelessly toil away for minimum wage. Walter wanted his son to learn the merits of hard work, much like he learned growing up in Mississippi. Even with race, Payton took the high road. The most prominent incident being his father’s tragic death in 1979, where Edward Payton was wrongfully arrested by police under the suspicion of driving under the influence, thrown into jail and died a few hours later due to a rare aneurism. Walter was understandably called on by civil rights leaders to hold the white officers accountable, but he would steer the other way.

Tragically himself, Walter Payton passed away on November 1, 1999 due to a rare liver disease that stunned the world. Like a fallen hero, he now lives through the Walter and Connie Payton Foundation, which seeks to help underprivileged communities along with providing awareness for organ donations. Despite being deeply depressed himself, Payton never shuttered to show adoration to his fans and critics — embracing them in moments that he understood could have a lifetime of difference. In more subtle ways, he also stood up for civil rights, by helping integrate his high school and pro teams.

Like all imperfect idols — from Jimi Hendrix to Kurt Cobain, Tupac to Amy Winehouse—we will never truly know Walter, as his legend has been suspended in time, never to see the light of redemption. So every year when we witness the new Walter Payton “Man of the Year”, let’s remember the little we did know — the good, the bad and the ugly — and remember none of us are perfect, and if we have another day, how can we change that for the better?